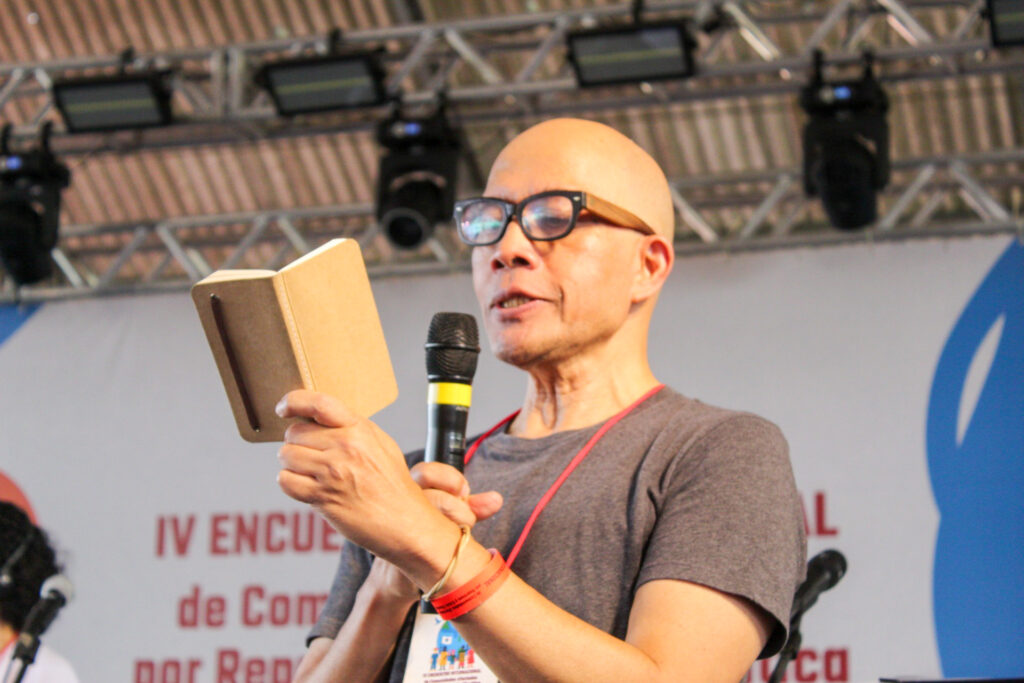

PROFILE | Hendro Sangkoyo: The guardian of the waters and memories of the islands

Hendro Sangkoyo, or “Yoyok,” as he likes to be called, came from Indonesia, in Southeast Asia, to participate in the IV International Meeting of Communities Affected by Dams and Climate Crisis, which takes place from November 7 to 12 in Belém do Pará, in the Brazilian Amazon. Involved in activism, teaching, and initiatives aimed at strengthening local communities, especially in Indonesia, Yoyok has a deep connection between knowledge, territory, and community life.

He grew up in Bali, where his family moved shortly after his birth. His mother was a very engaged activist, who involved him from an early age in the social issues of Balinese communities. While still young, Yoyo studied architecture and participated in student movements against the presidency, which were ultimately defeated and resulted in military intervention on campus.

He then spent some time on small islands, living with local communities, learning languages, and getting to know different realities. It was then that he realized that he “knew nothing about neighboring countries,” which prompted him to study the region and become a historian of Southeast Asia.

For many years, he pursued an academic career, teaching for five years in Melbourne, Australia, and then for two years in the US, at Cornell. But on May 29, 2006, an underground explosion caused by gas exploration changed his trajectory.

“My friends started calling me all the time. At that time, I was teaching in Ithaca, New York. With the explosion, the population didn’t know what to do, and every night, many people had to be moved and housed due to the mudslide. In a few weeks, the mud was already covering the roofs. That’s when I decided to return to Indonesia. I thought, ‘This is not my place. I don’t want to be a teacher, with all these privileges, and I have to go back.”

Back in Indonesia, Yoyok founded the School of Democratic Economics, where he works as an educator and student. The goal is to create a learning infrastructure for ordinary people, men and women who want to understand and tell their own stories.

The school operates on the basis of invitations from communities, with no ties to NGOs or external funding, operating autonomously since 2007, based on requests from the communities themselves.

Water as spirit and identity

Indonesia, an archipelago made up of more than 17,000 islands, is the fourth most populous country in the world. With a humid tropical climate and mountainous terrain, water is central to the survival and cultural identity of the island peoples.

“Living on an island requires a different approach to sustainability and environmental management than in large land masses such as Brazil, South America, or Asia,” says Yoyok. He explains the concept of the “water lens,” the underground freshwater reservoir on the islands. Over-exploitation of these lenses causes saltwater intrusion, leading to the death of vegetation and altering food regimes. Many small islands have been destroyed by this process, as is the case at the entrance to Jakarta Bay, where there are 105 islands, called the “Thousand Islands,” which are targets of interest for oligarchs and cronies of local presidents, who choose the islands they prefer and drill into the corals.

“Another thing that touches me deeply is Bali. Balinese indigenous knowledge values water as sacred and does not even call it water, but rather ‘tirtha’, which means sacred water. That is what I learned in my childhood. And when I returned, everything was a mess because of the World Bank’s 1970 master plan for Bali, which basically treated Bali as a mere commodity for tourism. This is where the aggression and abuse of the aquifer, groundwater, surface water, and everything that the indigenous peoples protected through rituals lies. In fact, Balinese religions are called ‘water religions’.”

Not all islands, however, share the same vision. Yoyok explains that in the Lesser Sunda archipelago, which stretches from Bali to the east, “there is no sense of belonging to the same island,” which creates conflicts among the inhabitants.

In just four decades, from 1970 to 2010, the entire aquatic landscape of Kalimantan was destroyed. The western part of Allegheny, with vast river landscapes such as the Mambramu River, now faces gigantic hydrogen production projects, and water scarcity in the region has been the trigger for several conflicts between local tribes.

Resistance amid repression

The political context in Indonesia shaped Yoyok’s trajectory. After the military coup in 1965, the government of Hadji Mohamed Suharto banned any association with Marxism and communism, causing students and young people to grow up in this repressive environment, without access to readings and discussions about Marx. In this vacuum, international organizations and NGOs, mainly funded by countries in the North, occupied the space of resistance, often trying to tame popular movements. “So, you are more polite in saying no,” he says ironically.

Back in Indonesia, his activism came to be seen as “out of the ordinary.” “At the School of Democratic Economics, the situations are funny, because we started to be these weird guys. We didn’t talk about money, but we worked hard, doing workshops in the field.”

Building solidarity between continents

With extensive international experience and networks of friends in different countries, Yoyok says: “I have adopted an internationalist mindset from the outset. That is why I have learned and built many networks of friends and colleagues. In Europe, for example, I have very close friends with similar ideas, who are directly opposed to the carbon market.”

This is not the first time Yoyok has participated in meetings in Latin America. He has already been present at activities in Colombia and at annual meetings in Montevideo, Uruguay, linked to the international forest defense movement. For him, there is something unique about Latin America. “There is greater identification and pride among activists in Latin America, something relatively rare in Indonesia, where there are challenges specific to a historically repressive context and external influences.”

Regarding the meeting in Belém, he highlights: “This opportunity to come together and join forces is extremely important for us to share experiences about the stresses and pressures caused by extractive operations and the energy industry, which affect our territories in Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Asia. So, I think it’s an important step toward strengthening resistance in the territory.”