From the River to Memory: The Strength of Women in Defense of their Territories and Cultures

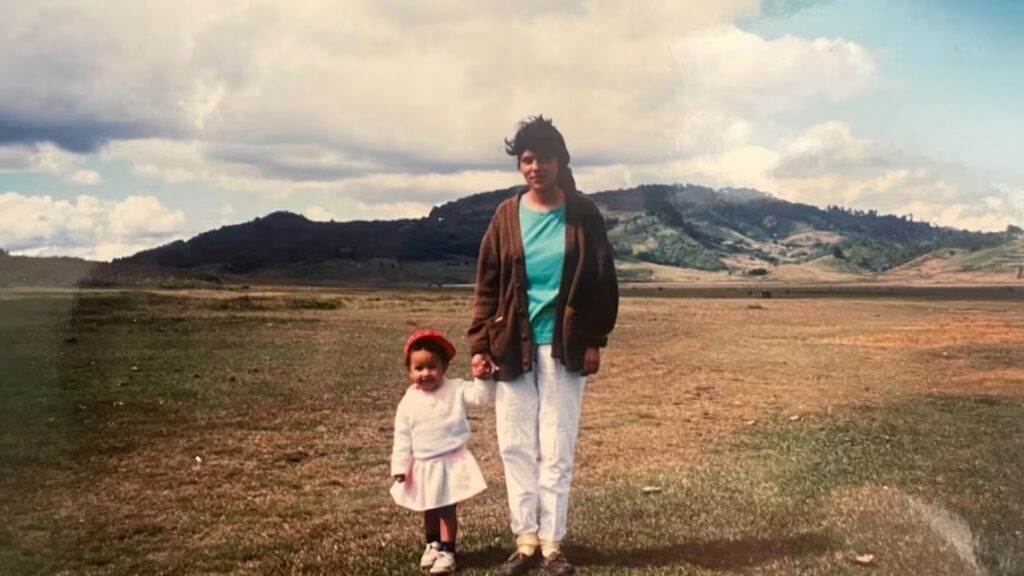

Daughter of Austra Berta Flores, a midwife and nurse elected mayor of La Esperanza, governor of Intibucá, and national deputy of Honduras, environmental and indigenous leader Berta Cáceres grew up surrounded by the strength of other women and a sense of community responsibility. From her earliest steps, she recognized that “the land is life,” and that defending the territory means defending the existence of her own people as an ethnic group.

A rural teacher and student activist in the 1980s, when Central America was bubbling with coups and guerrilla warfare, Berta helped found the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH) in 1993, at the age of 22. The organization would soon become the heart of the Lenca resistance against megaprojects, mining, and dams.

This direct confrontation with the advance of capital reached its peak against the Agua Zarca hydroelectric dam, which threatened to dam the Gualcarque River, a source of livelihood for the community, and of existence itself, as it is considered sacred to the Lenca. Alongside the communities, Berta did everything she could to protect the river and her people. She helped erect roadblocks, set up pickets, occupy properties, and investigate documents.

The pressure on companies and financiers was so intense that, in 2013, the Chinese giant Sinohydro, the main financier, abandoned the project. In 2015, Berta was recognized with the Goldman Environmental Prize, a kind of “Green Nobel Prize.” The price was high. Among 33 official complaints of death threats, Berta said that persecution had become part of the routine.

The assassination of Berta Cáceres

On July 15, 2013, COPINH, at the time led by Berta, held a protest against the construction of the hydroelectric dam on the Gualcarque River. This river, in Western Honduras, is considered sacred by the Lenca indigenous community, but no one from the company interested in the construction had consulted the population. The company, Desarrollos Energéticos Sociedad Anónima (DESA), is owned and controlled by one of the most powerful families in Honduras: the Atala Zablahs. The Honduran army, at the request of DESA, was protecting the site.

During the protest, soldiers opened fire on the demonstrators and killed Tomás García. Almost three years later, on March 2, 2016, gunmen stormed Berta Cáceres’s house and assassinated her. Her death was followed by the assassination, on March 15, 2016, of Nelson Noé García, also from COPINH. On October 18, 2016, the assassinations of José Ángel Flores and Silmer Dionisio George, of the Unified Peasant Movement of Aguán (MUCA), took place.

Following the assassination, a joint campaign to demand justice was launched by COPINH and the Cáceres family, with the support of organizations around the world. Even under immense international pressure, Honduran investigators at the time limited themselves to arresting the main perpetrators of the shootings and some of their immediate masterminds. Berta’s killer and some of those responsible were sentenced to prison terms ranging from 30 to 50 years.

The convictions, however, did not close the case. None of the masterminds of the crime were arrested. The evidence presented in court – including telephone records and WhatsApp conversations – shows, quite conclusively, that these assassins (many of them veterans of the Honduran army) acted on the orders of DESA executives. None of the company’s owners, including members of the oligarchic Atala Zablah family, who were part of these WhatsApp chats, have been charged with any crime.

In 2022, Roberto David Castillo Mejía was convicted as an intellectual co-author, for his role as president of the DESA company. Despite the convictions, activists are pushing for trials against the Atala Zablah family (the owners of DESA) who are accused of having commanded the criminal structure behind the crime.

“Fear Cannot Paralyze Us”

At the time of her mother’s assassination, Bertha Zúniga, affectionately known as Bertita to everyone, was 25 years old and pursuing a master’s degree in Mexico. The young woman took on her mother’s legacy of struggle, interrupted her studies, and assumed the general coordination of COPINH. At 27, she was already recognized as one of the strongest voices of Latin American indigenous youth.

“Fear cannot paralyze us. This is a fight for the rights of an ancient people, but also for justice for my mother and for personal reparation,” she said.

Bertita is a young woman with tender eyes and a firm voice. She learned early on that community life and political struggle are inseparable, neither as a way of life nor as the space where that life is lived. Just as she herself is inseparable from the river and the land that give meaning to her journey. She grew up among rivers and mountains, protest signs, and the smell of tear gas launched by the police. She remembers her mother taking the children to the villages so they would learn to value the land and their roots. “The threats were so frequent that we ended up finding it normal to live like that. Living in the forest and being threatened was equally normal for us,” she recalls.

Today, Bertita dedicates her time to working in the COPINH office, visiting communities, and constantly traveling to Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras, where she follows up on demands for justice and political negotiations. An important leader, this young woman transcends the boundaries of her community, city, and country, frequently attending international events where she does crucial work holding funders from the Global North accountable for the appropriation of Indigenous lands and natural resources.

None of this is possible without the company and care she gives and receives from her grandmother, Austra Berta Flores, now 92 years old. Bertita was raised by her mother and her mother’s mother, and lived with her matriarch for 17 years. Today, she takes care of her grandmother, time she insists on dedicating to the person who helped shape her.

“We are connected. I never stop being with her and taking care of her. Just as I always want to be here in this corner, in the middle of this forest, with these people. If necessary, I gladly pack my bags and leave for the struggles that need to be fought elsewhere. Because if capital and violence are organized around the world, our hope and work must be too.”

However, her routine is marked by insecurity. “Despite some changes in the current government, the structural problems remain and the violence against land defenders continues,” she says. She denounces an aggressive criminalization campaign: more than 3,200 publications, some with fake images of her bloodied face, produced with artificial intelligence. “They even released confidential information about my precautionary measures, obtained from a state institution. This increases our vulnerability.”

The International and Popular Struggle

At the helm of COPINH, Bertita expanded the battles beyond Honduran borders. In 2018, she filed a complaint against the Netherlands Development Bank (FMO), accusing it of co-responsibility for her mother’s murder, since the bank financed DESA even after knowing about the threats against the Lenca.

To date, nine people have been convicted of the crime, including company executives. But, for Bertha, these advances only occurred due to international pressure. “Justice will not come from the will of a state that persecuted my mother. If we don’t maintain global attention, the case may go unpunished.”

Her presence in global forums aims precisely to prevent them from being forgotten. “Organizing popular movements internationally is an act of hope. The problems we face in Honduras are similar to those in many parts of the world. Gathering, analyzing, and sharing strategies is essential, even without a single formula.”

The Honduran Coup

The story of the Cáceres women and the struggle of the Lenca people is dramatized through the coup d’état in Honduras. On June 28, 2009, President Manuel Zelaya was deposed by the military and sent to Costa Rica, on the same day he intended to hold a popular consultation to convene a Constitutional Convention. His opponents claimed that the initiative was an attempt to seek re-election, prohibited by the Constitution. Congress, opposed to Zelaya, declared “abandonment of office” and appointed Roberto Micheletti as interim president.

The coup was widely condemned by international organizations – the UN, the OAS, and Latin American governments – but never reversed. Elections held months later, under heavy repression, brought Porfirio Lobo to power.

The consequences were profound: increased political violence, persecution of social movements, censorship of the press, and assassinations of leaders. The coup opened a cycle of instability that still deeply marks the country, with a high rate of violence. Years later, Zelaya returned to the country and became an active political figure, while his wife, Xiomara Castro, was elected president in 2022.

In 2009, Berta Cáceres reflected on the motives behind the coup: “Because the rich, the oligarchs, the far-right – advised by the Miami mafia, the Cuban and Venezuelan counter-revolution, which [also] advise these coup plotters – what worried them was the possibility that the Honduran people could decide on strategic resources, such as water, forests, land; on our sovereignty, labor rights, the minimum wage, women’s rights – so that they become constitutional rights – the self-determination of Indigenous and Black peoples. So many things that we, as the Honduran people, dream of: the possibility of having an inclusive, democratic state and society, with equity and direct participation. The coup-plotting oligarchs know all this. That is why it is a coup. And this coup d’état is against all the processes of liberation of our continent.”

The Cáceres Women as a Work Ethic

Bertita sees her mother’s legacy in all spaces, both within and outside the Lenca people. In the COPINH communities, Berta Cáceres’ stories continue to be told as inspiration. Her voice, as a radio broadcaster and leader, continues to echo through popular radio stations. Her struggle is visible in the strength of Indigenous, Black, and peasant women, who challenge patriarchy every day.

In the immediate future, Bertha is preparing for the 4th International Meeting of People Affected by Dams and the Climate Crisis and the People’s Summit, events parallel to COP30, which will be held in Belém, in the Amazon. Before that, she will carry out activities in Colombia, before traveling to Brazil. “I’m already starting to pack my bags in advance and heading down,” she jokes.

“My mother transformed COPINH into a school of struggle and work ethic. Today, many young people are in the organization because they were touched by her message.” A message that reaches hundreds of indigenous people through the voice of Bertha the radio broadcaster.

Global Challenges

“COP30 is a great opportunity for civil society to exert pressure. We need to denounce the failure to implement climate measures and the false environmental solutions. I hope Brazil will have a strong voice, committed to the interests of the population, as Colombia has been in relation to Palestine,” says Bertha.

Speaking about the global situation, Bertha doesn’t hide her concern: “Human rights institutions have lost credibility by not responding to crises like the genocide in Palestine, but I believe that critical situations can lead to a greater social reaction.”

If Berta Cáceres, the mother, said that “whoever kills the earth, kills us too,” Bertha Zúniga, the daughter, repeats, in her own voice, that the project is not just hers: “I think so, this is my life’s mission. But it’s not just mine. It’s many people’s.”